A bird bath is essential in creating an inviting and welcoming environment for birds in a backyard. However, the right material used in making bird baths can enhance their durability, keep birds safer, and make cleaning them easier. Bird baths can range in style significantly, from classic stone designs to the more modern of recycled materials.

Some materials are ideal to use during the winter, while others are ideal to be used at all times of the year. The additional importance of a quality bird bath goes beyond just drawing a range of birds, as it beautifies your garden or yard. Therefore, you must choose the best material for bird baths carefully. This is what we will discuss in this guide. So, continue reading it till the end!

Why Bird Bath Material Matters?

Your choice of bird bath material affects:

What is the time span of the outdoor bath?

Can it withstand hot summers and frigid winters?

How simple is cleaning?

How secure do the birds feel?

The general appearance of your garden.

Not every bird bath material is created equal. While some are durable yet difficult to move, others are lightweight but delicate. Let's explain the most popular choices. And if you’d prefer a ready-made option, you can always check out the Birdfy Bath we’ll introduce later on.

Best Materials for Bird Baths

Now, we will share some of the best materials for birdbaths.

1. Stone Bird Baths

Stone is a traditional bird bath material. It is natural and fits in with gardens and landscapes.

Benefits:

Long-lasting and weather-resistant.

Offers a natural, earthy appearance.

Sturdy and heavy, preventing tilting.

Considerations:

May need occasional cleaning to avoid algae.

This bird bath can be costly.

Stone is among the most ideal materials for an outdoor bird bath. You may also mix in a layer of smooth stones or pea gravel to add a drainage level and texture, which birds also love.

2. Concrete Bird Baths

Concrete Birdbath is among the favourites of those who are interested in making a concrete bird bath. You can customise this material in terms of shape, size, or texture.

Benefits:

Exceptionally strong and substantial.

It can be shaped into distinctive patterns.

Perfect for outdoor use throughout the year.

Considerations:

If not sealed, it may crack in cold weather.

It needs upkeep to prevent the accumulation of moss or algae.

Concrete is an excellent material to use in a winter bird bath setup when properly sealed and insulated. You can even make a DIY birdbath using recycled concrete materials to create environmentally-friendly designs.

3. Ceramic and Pottery Bird Baths

Ceramic or pottery bird baths are elegant and handcrafted. They are rich in colour and stylish designs.

Benefits:

Decorative and fashionable.

Cleaning is made simple by smooth surfaces.

It is portable due to its low weight.

Considerations:

Fragile and prone to chipping.

It may crack in frigid temperatures.

Bird baths made of ceramic are suitable for use in gardens that are protected against frigid winters. For further stability, choose the heavy and thick ceramic.

4. Metal Bird Baths

Metal is a suitable material for setting up bird baths outside your home. Popular metals are stainless steel, copper, and aluminium.

Benefits:

Durable and weather-resistant.

Stylish metallic finish.

Portable and lightweight alternatives.

Considerations:

This material may corrode if not coated or treated.

It may get hot in direct sunshine.

Cooper birdbaths acquire an attractive coating as they age. Stainless steel fits well with the contemporary garden theme.

5. Plastic and Resin Bird Baths

Bird baths made of plastic or resin are flexible and cheap. They are also lightweight and likely to resemble stone or metal.

Benefits:

It is portable and lightweight.

Resistant to freezing and cracking.

Simple to maintain and clean.

Considerations:

Compared to metal or stone, it is less durable.

It may fade in intense sunshine.

Resin models are excellent materials for a bird bath because they are stylish and durable.

6. Bird Bath Recycled Materials

Green solutions are ever-increasing. Recycled materials that can be used for a bird bath include repurposed plastic, metal, and glass.

Benefits:

Environmentally-friendly material.

Distinctive and imaginative design.

Frequently portable and light in weight.

Considerations:

Durability varies by material.

More caution might be needed to guarantee safety.

Recycled bird baths can give a fresh twist of art and a current approach to the garden.

7. Pea Gravel Bird Baths

Any bath that has gravel added is safer for birds. A pea gravel bird bath offers a cosy perch and keeps birds from slipping.

Benefits:

This material increases traction.

Water is kept shallow for little birds.

Improves the natural appearance.

Simple to replace or clean.

Considerations:

Because trash, algae, and droppings can build up between stones, pea gravel needs to be cleaned frequently.

Larger birds may find the bath less stable and comfortable if the gravel fragments are smaller and more prone to shifting.

Using pea gravel to line your bird bath, regardless of the material, increases bird safety and creates a more welcoming space.

Tips for Choosing the Right Bird Bath Material

It is necessary to select the best material for a bird bath.

Materials: Choose the most suitable material when deciding on the best material for a bird bath.

Durability: The material must be durable enough to endure the weather in your area.

Maintenance: Cleaning smooth surfaces is easy, but porous surfaces require more attention.

Safety: No sharp edges, no toxic finishing.

Aesthetics: Complement your outdoor style with the bird bath.

Winter Use: For colder climates, heavier, freeze-resistant materials are preferable.

Pea Gravel Layers: Pea Gravel bird bath layers improve drainage and reduce algae growth, making it safer for birds.

The Best Material for a Winter Bird Bath

The best material for winter bird baths is one that doesn't freeze or crack as the temperature drops. Glass or ceramic are less effective than stone, resin, or other types of plastic. Concrete can work if it is properly sealed. When these materials are paired with a heater, birds can enjoy fresh water even in the coldest months.

The Best Material for an Outdoor Bird Bath

Durability is essential in outdoor environments. If you want a permanent installation, stone or concrete is the best material for outdoor bird baths. Otherwise, if you need something lighter, resin works great. Take into account your climate; resin doesn't fracture in the cold, whereas stone tolerates heat well.

Birdbath Maintenance Tips

No matter the material, regular care ensures birds stay safe:

Clean the bird bath weekly with mild soap and water.

Replace water daily to prevent mosquitoes.

Protect winter bird baths with heaters or bring lightweight baths indoors.

Check for cracks or sharp edges to avoid injuring birds.

A well-maintained bird bath extends the life span of any materials used in such a construction and keeps your feathered friends well satisfied.

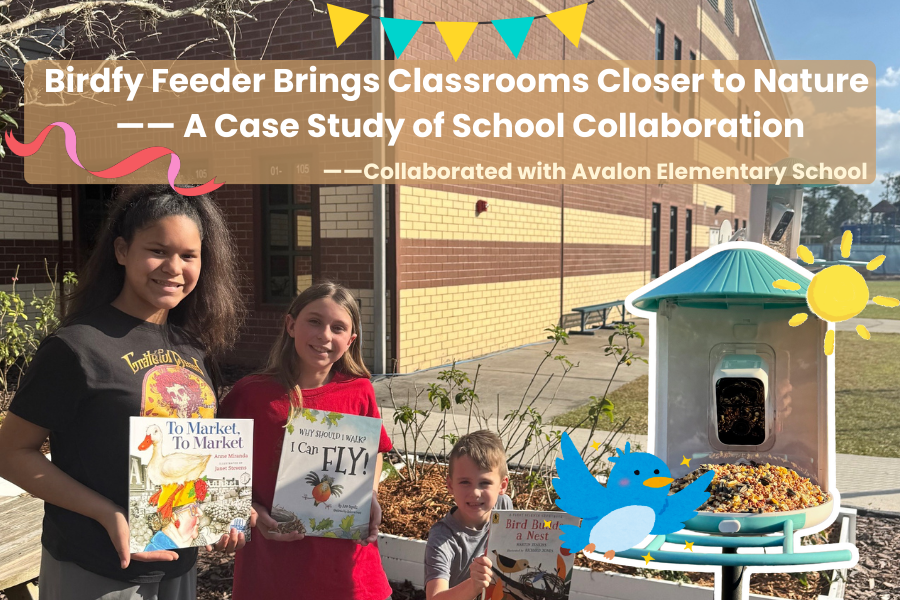

Best Recommendation to Buy – Birdfy Bath Pro

Birdfy Bath Pro is the best option when bird lovers need technology and nature combined in one product. Not only is this smart bird bath powered by the sun, but it also has a camera integrated with AI, so you can see your feathered friends in real time. It keeps the water fresh, draws more birds, and captures their wild beauty in high-quality video.

Key Reasons to Buy:

Durable & Safe Material: Crafted from UV-resistant ABS with 20% recycled content, ensuring long-lasting, eco-friendly, and bird-safe use.

Dual-Lens Capture: Wide-angle for lively videos + portrait lens for feather-detailed close-up photos.

Real-Time Alerts: Instant notifications whenever a bird visits your bath.

Eco-Powered: Built-in solar panel and rechargeable battery for continuous, sustainable operation.

AI Bird Insights: Identify 6,000+ bird species, turn your backyard into an educational paradise. [AI Version]

Shop Now

Conclusion

Selecting the best bird bath is a matter of the climate you live in, your aesthetics, and the bird bath maintenance. Concrete and stone provide durability and rigidity, but this is more likely to be present using ceramic and glass, which are more beautiful but have less durability. Metal is elegant, plastic is cheap, and recycled materials are eco-friendly. Ensure adding pea gravel for bird safety.

Nevertheless, if you want to get all the advantages, Birdfy Bird Bath is the best option. It will not only provide a safe environment but also it will give birds the chance to drink, bathe, and bring life to your garden throughout the year. So, get it right now!