Do Robins Migrate? Understanding Robin Migration Patterns

The American Robin is one of North America's most familiar and beloved songbirds. Its cheerful song, heralding the arrival of spring, and its presence on lawns across the continent make it an icon. However, the robin’s life is far more dynamic and complex than its humble reputation suggests. A common question that arises as seasons change is: Do robins migrate? The answer is a fascinating and nuanced yes. The migration of the American Robin is a story of adaptation, strategy, and the relentless pursuit of survival.

Do Robins Migrate?

Yes, but not all robins migrate. The American Robin is a classic example of a "partial migrant." This means that while a significant portion of the population undertakes seasonal journeys, another portion may remain resident year-round in the same area.

This decision is driven primarily by one factor: food. Robins are primarily frugivorous (fruit-eating) in the fall and winter, switching to a diet rich in earthworms and insects during the spring and summer. Whether a robin migrates depends on the local winter supply of berries and other persistent fruits.

- Resident Robins: In parts of their range where winter food sources are reliable—such as the Pacific Northwest, the coastal areas of the Northeastern United States, and many urban and suburban areas—robins may not need to migrate. They form large, nomadic flocks that move from one fruit-heavy area to another within a region, but they do not make a long-distance south-north journey.

- Migratory Robins: For robins breeding in the northern reaches of North America (Canada, Alaska, and the northern U.S. states), winters are harsh and snow cover makes finding food impossible. These robins are almost entirely migratory. Their journey is not a matter of choice but a necessity for survival.

This partial migration strategy creates a dynamic where a robin spotted in January in Pennsylvania might be a hardy year-round resident, a migrant from further north just passing through, or one that has chosen to winter there.

When Do Robins Migrate?

The timing of robin migration is less about a specific date on a calendar and more about environmental cues. However, general patterns can be observed.

When do robins migrate south?

Southward migration is a prolonged and leisurely affair compared to the spring rush. It begins as early as August, but the main movement occurs from September through November. This migration is triggered by the declining daylight hours and, most importantly, the dwindling supply of insects and the ripening of autumn fruits which provides the fuel for their journey. It’s not a single, coordinated exodus but a slow, wave-like movement.

When do robins migrate north?

The northward migration in spring is more conspicuous and eagerly anticipated. It typically begins as early as February and can continue through May. Male robins usually lead the charge, arriving first to establish and defend their breeding territories. Females follow a few weeks later. This migration is spurred by lengthening days and the warming temperatures that promise a thaw and the return of accessible insects and worms.

Where Do Robins Go in the Winter?

So, where do robin birds go in the winter? The migratory population fans out across the lower 48 United States and into Mexico. Their winter range is extensive, covering nearly the entire continental U.S., though they are far less common in the deepest southern parts of Florida and Texas. Some robins travel as far south as central Mexico and the Gulf Coast.

Crucially, their behavior in winter is strikingly different from their solitary or paired breeding behavior. In winter, they become intensely social. They form large, roaming flocks—sometimes numbering in the hundreds or even thousands—that move nomadically across the landscape. These flocks seek out and descend upon sources of berries: holly, juniper, crabapple, hawthorn, and pyracantha, among others. A single tree can serve as a temporary banquet hall for a massive flock before they move on to the next food source.

This leads to the specific question: Where do robins go in August? August is a transitional month. For many northern robins, it marks the very beginning of the southward movement. However, they are not yet in their deep winter mode. In August, you are likely to see robins gathering in early post-breeding flocks. They become quiet and secretive as they molt their feathers, a process that leaves them vulnerable. They are often found in woodlands and dense thickets, feasting on early-ripening fruits to build up fat reserves for their impending journey. They are preparing to go, not yet gone.

How Far Do Robins Migrate?

The distance a robin travels is highly variable and depends on where it began its journey. A robin breeding in Alberta, Canada, might migrate over 2,000 miles to winter in East Texas. Research, including tracking studies using geolocators, has shown that some robins make impressive journeys. However, a robin from Massachusetts might only travel a few hundred miles to winter in New Jersey or Virginia.

On average, most migratory robins likely travel a few hundred to a thousand miles. They do not make non-stop, trans-oceanic journeys like some warblers or shorebirds. Their migration is characterized by shorter "hops," moving at a slower pace and feeding heavily on fruits along the way to replenish their energy stores.

Do Robins Migrate in Flocks?

This is a key distinction between their seasonal behaviors. Do robins migrate in flocks? Yes, absolutely. While they are highly territorial and solitary during the breeding season, migration is a social activity. They travel in flocks, often at night.

There are several advantages to this strategy:

- Safety from Predators: There is safety in numbers. More eyes and ears make it harder for a hawk or owl to launch a successful surprise attack.

- Efficient Foraging: A large flock can quickly locate and efficiently exploit concentrated food sources, like a berry-laden tree.

- Navigation: While the exact mechanisms are still studied, it's believed that migrating in flocks may aid in navigation, perhaps by following more experienced individuals.

The image of a large, chattering flock of robins descending on a winter berry tree is the quintessential portrait of the non-breeding robin.

Tips: Observe Robins During Migration

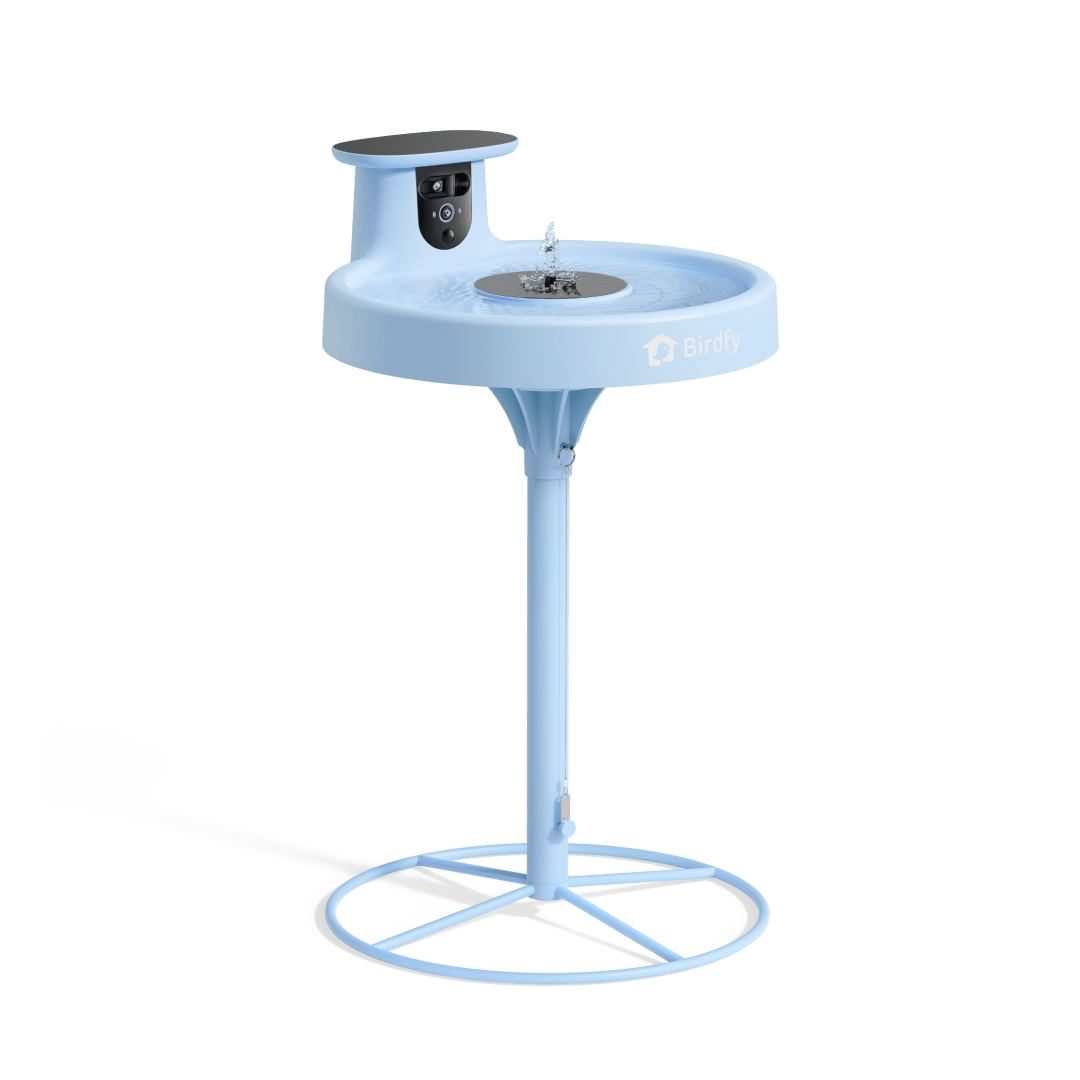

Whether robins migrate through your area or choose to stay year-round, having a way to watch them up close makes the experience even more rewarding. This is where the Birdfy Smart Bird Feeder with Camera comes in.

Here is the world's first award-winning, dual-lens smart bird feeder - Birdfy Feeder 2 Pro. With this great bird feeder, you can:

- Provide fresh food for robins during the winter.

- Watch robins up close as they visit your backyard.

- Identify robins and 6,000+ bird species with AI-powered recognition.

- Record clear details with 1080P&2MP feeder camera.

- Support robins year-round thanks to a weather-resistant, IP66 design.

By setting up a Birdfy bird feeder, you’re not only helping robins during their seasonal journeys but also giving yourself a front-row seat to one of nature’s most fascinating migrations.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Herald of Spring

The American Robin’s migration is a testament to the incredible adaptability of nature. It is not a simple, uniform event but a flexible and complex response to environmental conditions. Some stay, some go. Some travel far, some move just a short distance. They change their diet, their social structure, and their entire way of life with the seasons.

Understanding this complexity deepens our appreciation for this common bird. The next time you see a robin on a frosty winter morning, you are not looking at a bird that is hopelessly lost or confused by a changing climate. You are likely looking at a hardy resident or a weary traveler from the far north, expertly surviving on nature’s winter bounty. And when you hear that first cheerful song in early spring, you are hearing the triumphant return of a migrant, a survivor who has completed an epic, unseen journey to begin the cycle of life anew.

Share