Moult in Birds

At this time of year, birds start to look rather odd, and may also seem to vanish from our gardens and backyards for days or even weeks on end. That’s because they are moulting into their new set of feathers in preparation for the autumn and winter months ahead.

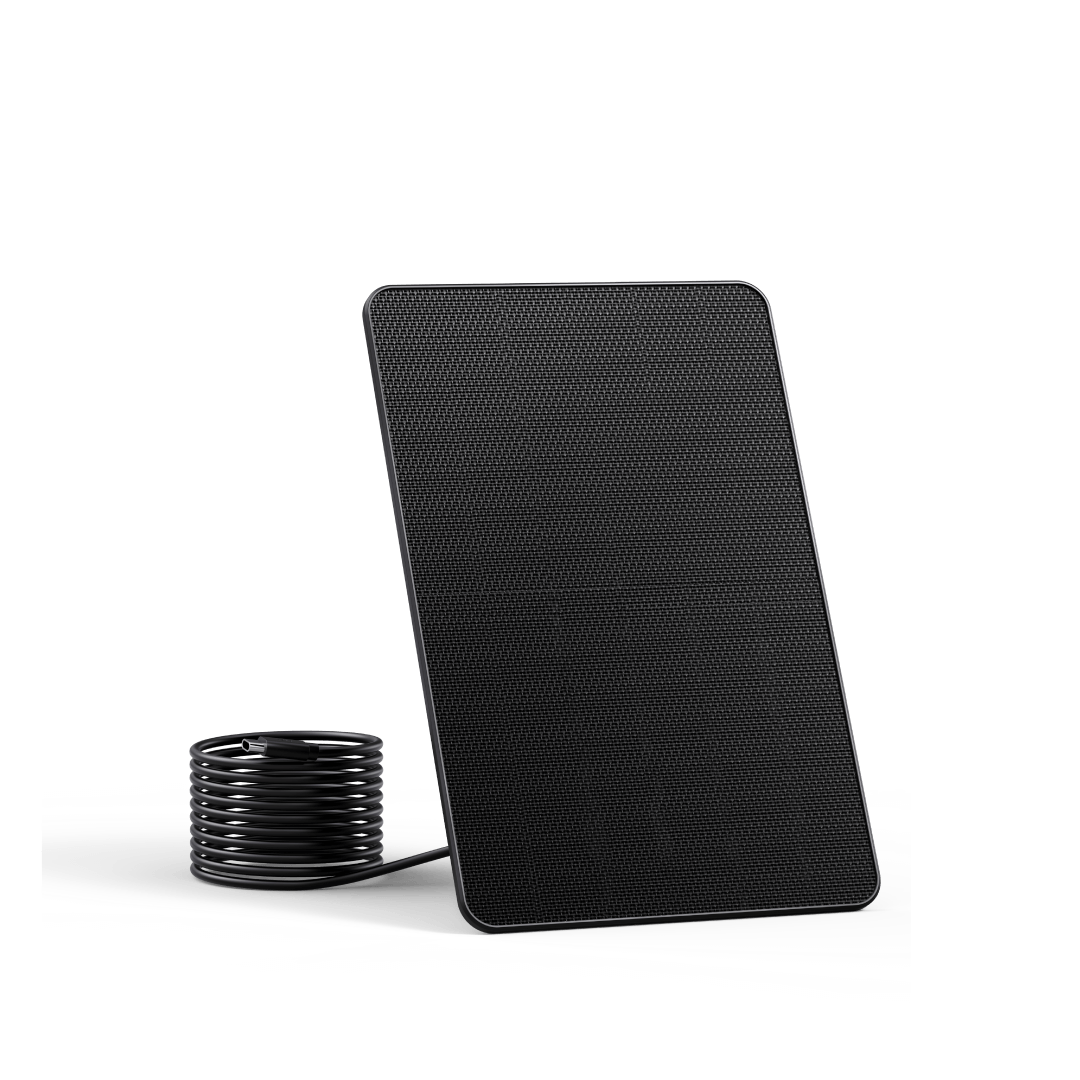

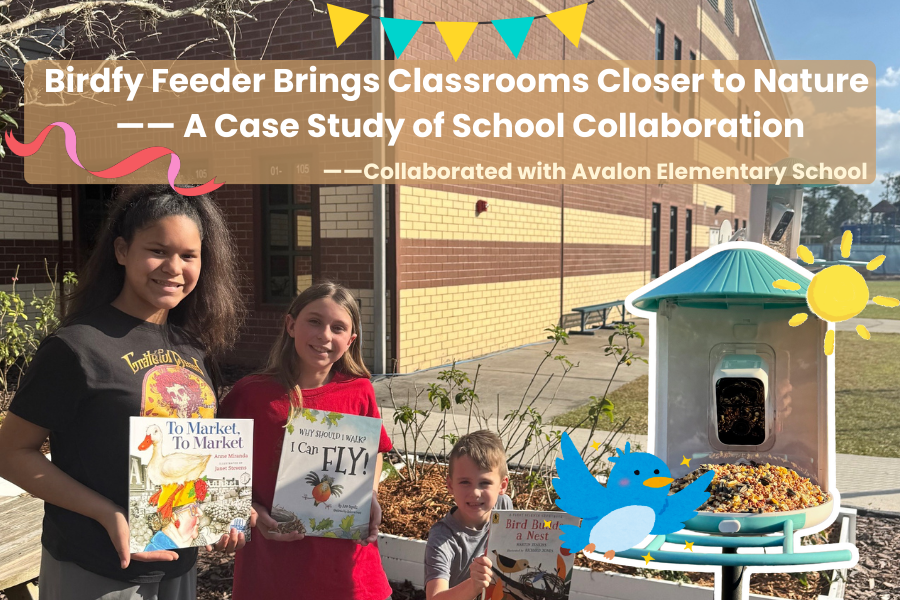

By July, most garden and backyard birds have finished breeding, and by now have raised one, two or perhaps even three broods of chicks. But take a look at them on your Birdfy camera footage and you might wonder what’s going on.

Colourful birds like cardinals and blue jays, or robins and blue tits, appear to have lost their pristine appearance and, to be honest, look rather tatty and unkempt. Their once pristine feathers may be fluffed up or even missing, giving them a very unattractive appearance compared with earlier in the year.

There are two reasons for this. The first is that the adult birds have been run ragged – almost literally – for the past few months, as they rush around to find enough food for their hungry and demanding chicks. They may go back and forth, to and from their nest, several hundred times a day; and barely have time to find enough food for themselves. Quite simply, they are exhausted.

The other, related reason is that they have begun the long and complex process of moult: shedding their old feathers and replacing them with new and fresh ones. Most songbirds – the vast majority of species that visit our Birdfy camera feeders – moult once a year, almost always in summer, for reasons I will explain later.

Why Moult?

For any bird, their feathers are what makes them unique. Other creatures – such as bats – can fly, and several species of bird do not. But all birds – and no other creatures on Earth – have feathers.

Feathers are one of nature’s miracles. Light yet strong, they allow birds to get and stay airborne; to manoeuvre themselves once they are in the air; and to keep warm, especially on cold winter nights.

But to work properly, feathers must be kept in tip-top condition. Birds do so by preening regularly, using their bill to smooth out the contours along each feather to make sure each one works as well as it can.

Preening will help, but once the feathers begin to wear out, their effectiveness declines. If a bird did not then moult and replace their old, worn and damaged feathers with new ones, they run the risk of being unable to fly properly, putting them in danger from predators. Even if they do survive, they are then unlikely to make it through the winter as their feathers will not be able to trap enough air to keep them warm.

That’s why, at this time of year, small birds undergo a full moult, replacing all their feathers.

Why moult in summer?

By July, the hard work of the breeding season is mostly over, the days are still long – especially the further north you go in Europe or North America – and there is still plenty of food; both naturally available and that provided by us in our bird feeders and feeding stations. So if you are a bird, this is a good time to take a break from all that hard work and get your plumage back into shape.

Food is vitally important for moulting birds because replacing their old, worn feathers with neat, new ones takes a lot of energy – so it’s not something to be done in the winter months when the short daylight hours and cold weather make finding enough food difficult, without the added complication of moulting at the same time.

Another reason to moult at this time of year is that with so much foliage still on trees and bushes, birds that have shed some of their feathers and grown new ones – making it harder to fly away when avoiding predators – can hide away while they feel vulnerable.

After moulting

Some birds that visit your gardens, backyards and Birdfy camera feeders are residents – they will stay with you – or at least in the same locality – all year round. Depending on where you live, these can include robins (both the American and European species), thrushes, blackbirds, tits, chickadees, finches, sparrows, buntings, crows and jays, and woodpeckers.

All these resident species face a challenge: as the days get shorter and the temperatures drop, they need to be in the best possible physical condition to find food and convert that into energy. This means their feathers need to be new and in good condition.

Other species are migrants – they fly south in the autumn, either heading from the USA and Canada to overwinter in the warmer southern states of the USA, or going as far as Central or even South America; a journey that may be several thousand miles and many days or weeks in duration. They too need their feathers to be in tip-top condition, to make sure that they can fly efficiently, avoid predators and keep their energy levels up for this epic journey.

So by September and October, take a good look at the birds on your feeders, and note what great condition they are in – whether they are about to head off for the winter or stay put with you!

Do birds moult again in the same year of their life?

Many birds do moult just once a year: these include birds of prey, thrushes, swallows, woodpeckers, flycatchers and hummingbirds.

Others have their main moult in the summer after breeding, but then have a partial moult the following spring, just before the breeding season starts again. This tends to be birds whose males have a smart and bright breeding plumage, and become less colourful in autumn and winter. In North America, this category includes buntings, tanagers and warblers. A very few species – including the Bobolink and Marsh Wren in North America, undergo two full moults each year.

Share