April Blog for Birdfy:Spring Migration

Guest Article from BirdWatching Ornithologist

How to find new species for your list every day this month

One of the first signs of spring, in the UK in particular, is the arrival of migrant birds, which will spend the warmer months of the northern hemisphere year here. From the first few Sand Martins, Wheatears and Chiffchaffs in March, this migration builds to a peak in the second half of April and into May.

Why do birds migrate in spring?

So why does this huge movement take place? Put simply, the birds involved spend the northern hemisphere autumn and winter in warmer climates, sometimes in southern Europe and North Africa, but in many cases south of the Sahara, as far as the tip of South Africa. Many of the Swallows that we see in the UK in summer, for example, spend part of the year down around the Cape. They do so because food is easier to find in such places. The movement back to the northern hemisphere in spring is to take advantage of plentiful food here during the warmer months as they try to raise a family, with insect food particularly important – pretty much all songbirds need insects to feed their young on.

How do birds migrate?

It still isn’t fully understood exactly how all birds perform their migrations, but it’s thought that many navigate over long distances by following the earth’s magnetic field, which they are far more sensitive to than us humans. But they also follow visual cues, once they get relatively close to their destination, following the lines of rivers and even motorways, or navigating towards prominent hills and mountains. They may even use smells, too.

Many species migrate in relatively short ‘hops’, stopping regularly to eat, drink and sleep, and this is obviously easier for birds such as ducks, geese and seabirds, which can safely land on the sea and take off again. Those birds who can’t will usually make a stop just before they have to cross any large stretch of water, and many will also cross water at the narrowest point. So, for example, the Straits of Dover are a major crossing point, while further south, the Straits of Gibraltar see huge numbers of migrants passing through.

Do all birds migrate in spring?

Not all birds need to make a migratory journey in spring. Some species remain around their breeding areas all year round – this is true of many of the most familiar garden birds in the UK, such as Blackbirds, Robins, Blue Tits and House Sparrows. This is because they are generally able to find enough food to survive the winter, even in the coldest years, although more and more species take advantage of the helping hand that we can give them by filling up our garden feeders. The trend towards warmer winters in the UK means that individuals of some species, such as Blackcap and Chiffchaff, are starting to remain here in winter, rather than migrating and returning in spring, and it may be that more species will start to do the same. But in other species, it can take a very long time for this evolutionary instinct to change. Ospreys, for example, could easily winter in the UK, as even in the worst weather there are always plentiful areas of unfrozen water to fish in, but they still migrate to west Africa in autumn, and return again in spring.

Does the temperature affect birds’ spring migration behaviours?

The exact timing of migration can vary due to the weather, although broadly speaking spring migration generally starts around mid-March and goes on until the end of May. Wind direction, rather than temperatures is usually the key factor. In the UK, southerly and south-westerly winds will bring large ‘falls’ of migrants crossing from the Continent, while northerly and/or easterly winds can hold up migration for a few days, with large numbers of birds waiting on the French coast for things to change. That said, favourable winds for migration usually bring warmer weather too, while unfavourable winds usually go hand in hand with cold temperatures. If bad weather persists well into spring, all species will eventually migrate anyway, as they have to find and defend breeding territories, find mates, and start raising families.

What are the best bird habitats during migration?

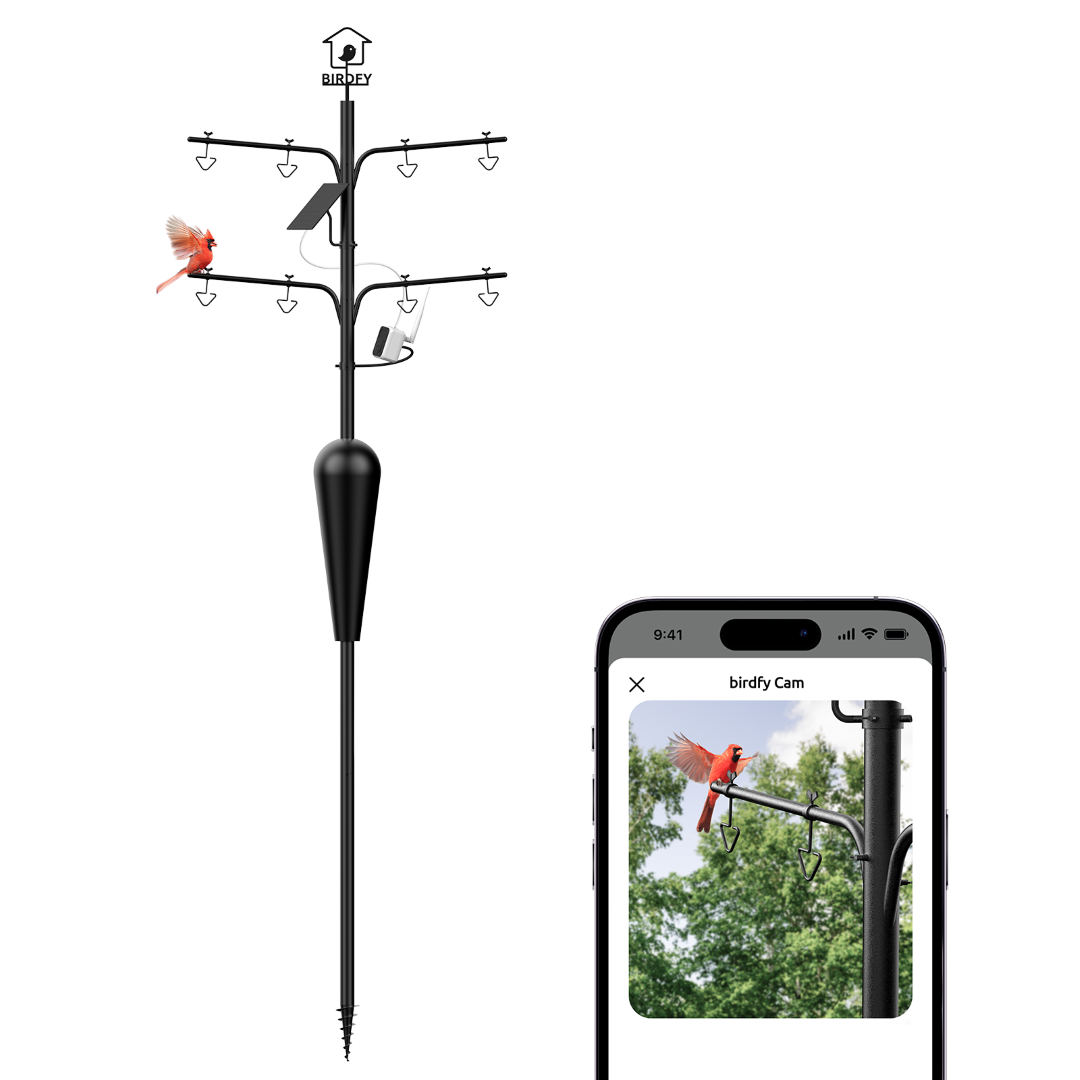

Three types of habitat stand out, After their journey, all birds need to restore energy levels, so anywhere with water is likely to attract a lot of migrants, both to drink, and to feed on the insects that are starting to emerge at this time of year. Areas with plenty of hedges, bushes and scrub are also favoured, as they provide safe cover for roosting in, as well as more potential food in the form of insects, invertebrates, and perhaps a few seeds and berries. Sites that combine the two, such as many reservoirs in the UK, are always hotspots for migrants. On a smaller scale, though, many people’s gardens also have the same attractions (assuming they have a pond or a bird bath), so be aware that pretty much any migrant can stop off pretty much anywhere at this time of year – just this last week we’ve seen reports of a Ring Ouzel (a species that breeds in bare mountain landscapes) in a suburban garden.

How to attract new species in your garden during migration season

Many beginner birdwatchers assume that the middle of winter is the time when they most need to provide food for their garden birds. However, except in the hardest of UK winters, there’s usually enough natural food (seeds and berries, mainly) around until the start of March. At that time, it becomes vital to provide food, to supplement dwindling natural food, and to allow resident birds that are starting breeding to focus all their attention on finding insect food for their young. But doing so also has the side benefit of making your garden attractive to passing migrants, especially songbirds. Keep your feeders and bird baths topped up, and if possible, also avoid trimming back hedges and bushes (autumn is the best time for this) – migrants will often drop into even the most urban of gardens for a rest-stop, or even when briefly grounded by a typically short but sharp spring shower.

How to find new species during migration

Outside your garden, there are a few easy tips to follow if you want to see new species during the spring migration period.

Firstly, try to visit a good variety of habitats, including those mentioned earlier, on a regular basis. Above all, definitely watch wetland sites, or any water bodies, very closely, but if you can’t easily get to such places, even an urban park has plenty of potential – last year, I saw Blackcap, Chiffchaff, Willow Warbler, Garden Warbler and Lesser Whitethroat within an hour in the middle of one of the UK’s biggest cities. Try to visit your area’s highest points, too – migrating birds often stop off at these, or at the very least will pass over at lower altitude.

Secondly, try to do at least some of your birding at dawn or dusk. Some species migrate by day, and many do so at night, but either way, these are times of peak activity, with birds feeding up just before taking flight, or just before finding a spot to roost for the night. Thirdly, and connected with the second point, try to learn a few bird songs and calls, as your first clue to the presence of migrants, especially unexpected ones, may well be sound. Some songbirds perform their full song even when stopping off on migration (Willow Warblers for example), while others, such as Redstarts, tend to use a shorter, simpler call instead.

Fourthly, remember that anything can turn up anywhere, and that at this time of year, birds appear in places that may appear at odds with the habitat a field guide says they favour. For example, Common Sandpipers, which breed besides fast-flowing upland streams and rivers, turn up beside all sorts of lakes and reservoirs in spring, and often favour the manmade dams and walls, while Yellow Wagtails can often be found at sewage works while migrating, though they breed on wet pastures.

Finally, persistence really is the key, especially where many of the commoner migrants are concerned. If you miss out on seeing them one day, try again, and again. While some species tend to arrive in the UK all at once, over a couple of days at most, a lot arrive over a much longer period. The most extreme example is probably the Wheatear – while I’ve yet to see one this spring, despite checking for the last month, they’ll be passing through my area for at least another month, so I won’t be giving up yet!