Understanding Female Eastern Bluebirds: Traits & Habits

The Eastern Bluebird, a symbol of beauty and joy, is often celebrated for its vivid colors and melodious songs. However, the female Eastern Bluebird, with her more subdued hues, holds her unique charm and plays a crucial role in the life cycle of this species.

What Does a Female Bluebird Look Like?

The female Eastern Bluebird possesses an understated elegance. Her soft grayish-brown head and back seamlessly transition into a gentle blue on the wings and tail. The breast, though not as vividly red as the male's, carries a warm, earthy tone, providing a subtle yet attractive contrast.They are small members of the thrush family, measuring from six to eight inches in length. They have large eyes, round heads, and slender, short bills which are wide at the base.

Bluebird vs. Robin/Blue Jay

The Eastern Bluebird, often confused with the American Robin, shares a similar size and rust-colored breast. However, Robins has a darker, grayish-black back and a longer tail.

Besides that, both the Bluebird and the Blue Jay are admired for their striking blue coloration, but they also differ significantly. The Eastern Bluebird is smaller, with a round head and a short, straight beak, ideal for its insectivorous diet. The Blue Jay, on the other hand, is larger and noisier, with a prominent crest and a stout, powerful beak, reflecting its more omnivorous diet.

Distinguishing Male and Female Bluebirds

The Eastern Bluebird, a small thrush native to North America, displays distinct sexual dimorphism. The male is renowned for his vivid, royal blue plumage and rusty red breast. In contrast, the female Eastern Bluebird exhibits a more subdued color palette. Her feathers are tinged with gray, blending blue and brown hues, particularly around the wings and tail. This subtle beauty enables her to blend seamlessly into the nesting environment, providing an extra layer of protection against predators.

What Are the Habits and Characteristics of Female Bluebirds?

Eastern Bluebirds, particularly the females, exhibit a range of fascinating behaviors and characteristics that captivate bird enthusiasts. These birds are renowned for their serene and sociable nature, often seen in small flocks, especially when not in breeding season. The calm and friendly disposition of Eastern Bluebirds makes them a joy to observe, offering a glimpse into a harmonious coexistence with nature. They communicate through a blend of subtle vocalizations and expressive body language, with the females known for their softer, more delicate songs. These songs and various physical cues, like wing flutters, are critical in their interactions, particularly during the nurturing of chicks or in communication with their mates.

The female Eastern Bluebird, a diligent and industrious creature, plays a pivotal role during the breeding season. Responsible for constructing the nest, typically in tree cavities or birdhouses, she lays three to six eggs per brood and is committed to their incubation. After the eggs hatch, both parents take up the task of feeding and safeguarding their young. Beyond breeding, the diet of these birds is versatile and seasonally adaptive, primarily consisting of insects and small fruits. They are adept hunters, catching insects in mid-flight, and switching to berries and fruits in the winter months when insects are less abundant. In the wild, a female Eastern Bluebird can live for 6 to 8 years, though some have been known to surpass this age, particularly when in an environment with plentiful food and fewer predators.

Where Can Female Eastern Bluebirds Be Commonly Found in the US?

The Eastern United States and parts of Canada are known as the preferred realms of the charming Female Eastern Bluebirds. These birds are often spotted in a variety of settings, ranging from open fields and gardens to the more secluded wooded areas. What makes these locations ideal is their abundance of perching spots and available nesting cavities, crucial for their survival and breeding. A deeper dive into their habitat preferences in the Audubon Field Guide reveals the United States Eastern Bluebird's remarkable adaptability, a trait that enables them to flourish in diverse environments. This adaptability isn't just limited to the vast rural farmlands; surprisingly, these bluebirds have also made their way into suburban areas, demonstrating their ability to coexist in closer proximity to human habitation.

How Can I Attract Female Eastern Bluebirds to My Garden?

Experience the joy of winter birdwatching! Female Eastern Bluebirds, renowned for their stunning beauty, can transform a snowy garden into a scene of vibrant life and color. Attracting these delightful birds to your garden not only offers a visually pleasing experience but also provides a sense of happiness and tranquility during the colder months.

Where Do Bluebirds Like to Stay?

Inviting the elegant Female Eastern Bluebirds into your garden can be a rewarding experience for any nature enthusiast. To create a habitat that these birds find irresistible, start by installing nesting boxes, which offer them a safe place to raise their young. Additionally, a consistent source of water, be it a birdbath or a small pond, is essential in making your garden an appealing spot for these birds. But what truly makes your garden a haven for Eastern Bluebirds is the availability of food. Planting native shrubs that yield berries, especially beneficial during the colder months, can be a natural way to attract these birds. For more insights into their habitat preferences and other interesting facts, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Eastern Bluebird offers an extensive overview.

What Do Bluebirds Like to Eat?

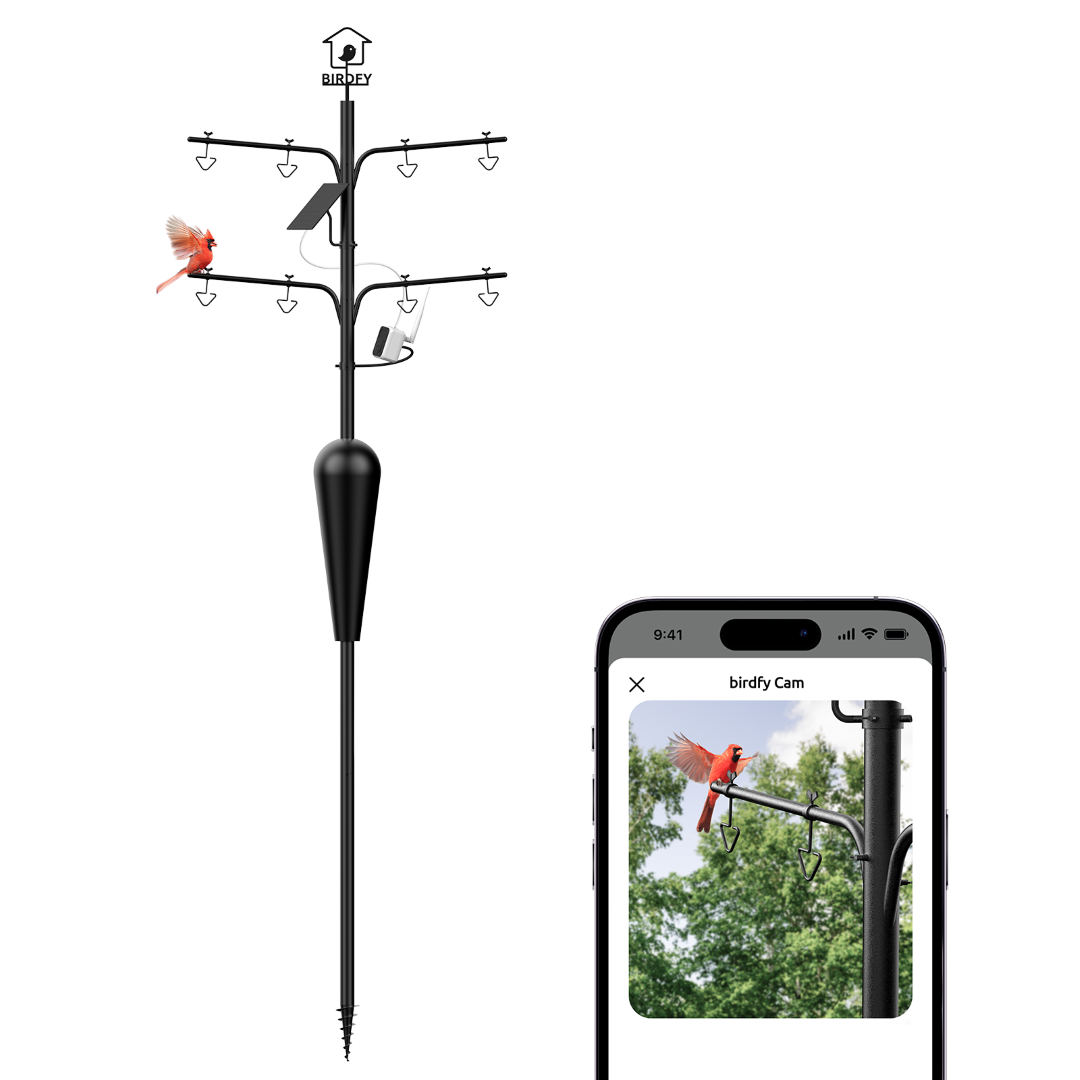

When it comes to the preferred diet of bluebirds, including mealworms, small fruits, and berries in your bird feeders can significantly enhance your chances of attracting them. It's important to remember that bluebirds are insectivorous; hence, maintaining a pesticide-free garden ensures a healthy population of insects, providing a natural food source for these birds. Creating such an insect-rich environment not only benefits the bluebirds but also contributes to the ecological health of your garden. To explore more about bluebirds and other bird species, visit eBird, a comprehensive birding database. Additionally, if you're looking for high-quality bird feeders that can attract bluebirds, check out Birdfy's selection of products.

![[Pre-order] Birdfy Nest - Smart Bird House with Dual Cameras](http://www.birdfy.com/cdn/shop/files/birdfy-nest-with-app.png?v=1701165422)

Comments

Jerry Bryson said:

Before our Birdfy camera feeder I would occasionally see the quick view of a Blue Bird. Now I see them every day, and yes, there is a small flock of them! I make sure that there are dried meal worms included in the feed and I have a wonderful watering bowl close to the backyard feeders, which is used every day, over and over by all the birds. It is cleaned daily and filled with fresh warm water in the colder months. Thank you for the informative article.