Stephen Moss: Breeding Birds

In what I call the annual ‘race to reproduce’, many birds only have one chance to have a family each year. But others hedge their bets, raising two, three or if they are able to, even more broods…

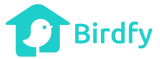

And especially for songbirds – which form the vast majority of the species we see on our Birdfy camera feeders – this time of year is even more crucial. Many species only live for one, two or if they are very lucky, three years, so this may be the only chance they get of passing on their genetic heritage to the next generation.

Raising a family is, quite simply, exhausting. A pair of small songbirds, like tits and chickadees, usually lay between 6 and 12 eggs. If all these hatch successfully the tiny, helpless chicks must be fed constantly, throughout the daylight hours. That might mean bringing back as many as one thousand items of food – mostly small caterpillars or other insects and invertebrates – every single day!

At the height of summer, with up to 16 hours of daylight, that works out at one item every minute of the day – or when the duties are shared, as they usually are, one item every two minutes brought back by each parent.

No wonder that by the time the chicks fledge and leave the nest, roughly 12 to 14 days after hatching, the parents look so tatty and exhausted. And yet some start breeding again almost immediately, layong a second clutch and raising a second brood of young.

1. All their eggs in one basket – single-brood species

In North America, many long-distance migrants such as the New World Warblers (family Parulidae), which arrive back in May having overwintered in Central or South America, only have a single brood – though oddly, Old World warblers (family Sylviidae) in Britain and Europe tend to have two.

Although having a single brood (often with larger clutches than other, multi-brooded species) has certain advantages – not least for the adult birds’ well-being and chances of survival – it also has risks. Breeding failures are often linked to a spell of bad weather: either a drought, or long spells of rain, both of which can reduce the availability of food, so that the chicks starve and fail to fledge.

With the climate crisis, the timing of our seasons is rapidly changing. That means that if the birds don’t respond to earlier springs, they may discover that by the time their young are in the nest the food supply has already peaked. And if they only have one brood – both literally and metaphorically putting all their eggs in one basket – then if a predator finds the nest and eats all the eggs, or kills all the chicks, then that is a disaster. (Though if it happens early in the nesting cycle, many pairs will start again, and this time be successful).

2. Doubling the odds – two-brood species

The risks they face may be why so many species of songbird have two broods. After all, this can literally double the number of chicks they raise – though in some species second broods are not usually as successful as the first ones.

Nevertheless, even if they only raise a few young to the fledging stage, they have at least increased their breeding success a little.

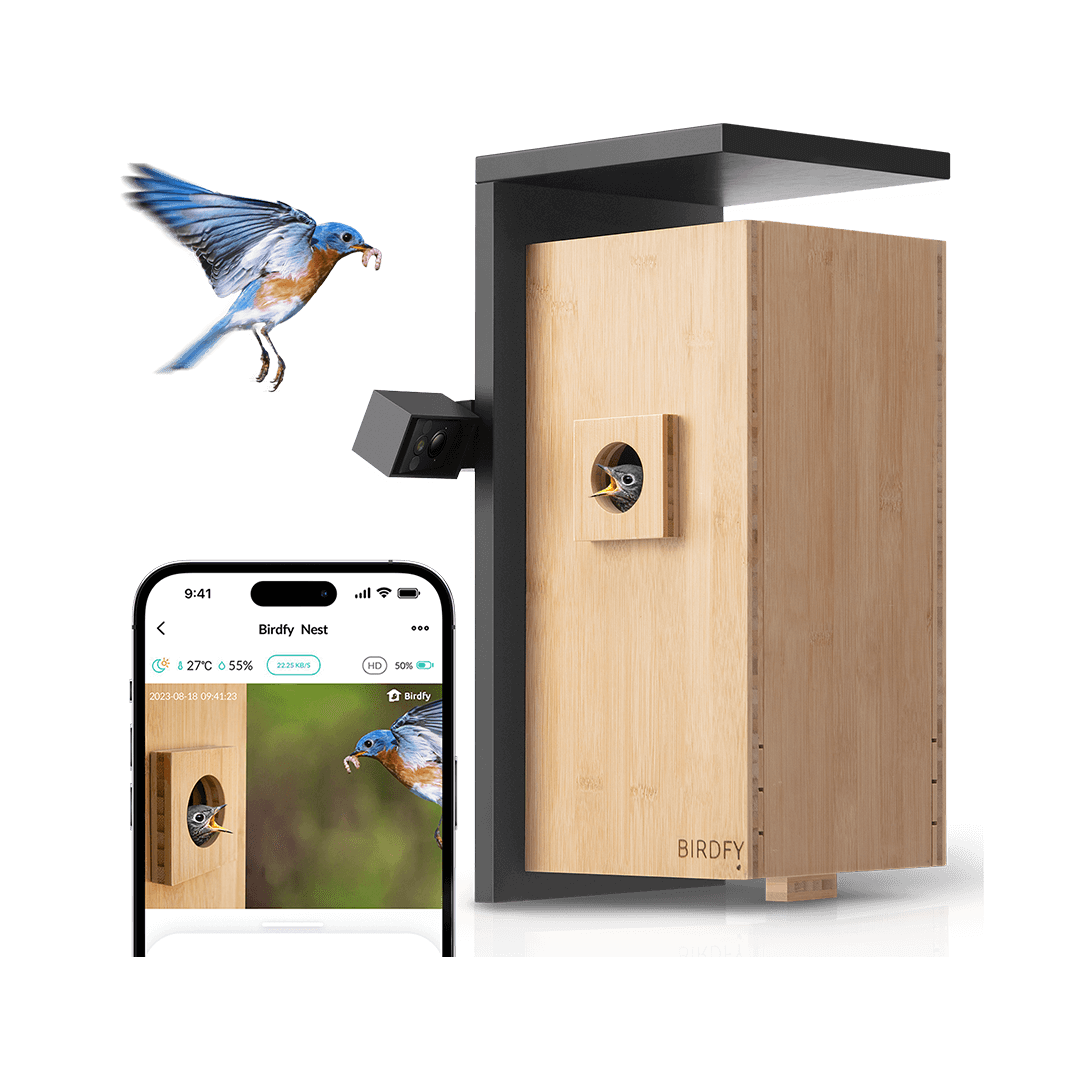

In North America, many common backyard birds, including American Robins, Northern Cardinals, House Wrens and Eastern Bluebirds, have two broods – in some cases, they manage to squeeze in three – while American Goldfinches, which start breeding later in the season, usually only have one brood, but on occasion manage two.

In Britain and Europe, resident species such as the Eurasian Wren and Pied Wagtail usually produce two broods, as do some migrants such as the Blackcap and Whitethroat.

3. Going for broke – multiple-brood species

In both North America and Europe, some species really go for broke! Barn Swallows, found on both sides of the Atlantic, will try for a third brood if the weather conditions allow it, and there is enough food to feed their hungry offspring.

This can be risky – chicks from the third brood might not hatch until September, when a cold and windy spell can make flying insects almost impossible to find, so that the chicks starve in the nest. And even if the chicks do fledge, they need to build up their strength very rapidly, to migrate on their epic journey south, from North America to South America or from Britain to Africa.

Resident birds such as the American Robin and Eurasian Blackbird often have three broods, especially when an early spring, with fine weather, allows them to raise their first brood by April (or sometimes even earlier).

In really good years, Blackbirds have been known to raise four or even five broods successfully, though with more unusual and unseasonal weather conditions that is becoming less frequent.

For some multi-brooded species, climate change is providing to be an unexpected advantage. A recent scientific study found that they are the current ‘winners’ of the climate crisis, as warmer, earlier springs provide them with more opportunities to breed. However, for long-distance migrants, which tend to return north at exactly the same time each year, earlier springs are a disaster, as it can cause them to mistime their breeding season and fail to raise any young at all.

4. The fight to survive

Even after a clutch of eggs has successfully hatched, the food supply has been plentiful and easily available, and all the young manage to fledge and leave the nest, the danger is far from over. Typically, having left the nest, a young bird has less than a fifty-fifty chance of making it through the coming autumn and winter and surviving until its first birthday.

This, however, is simply the way songbirds live their lives. Like the movie star James Dean, they tend to live fast and (usually) die young. However, there are always exceptions: some songbirds have been found to live until at least a decade old, and sometimes even longer.

5. How we can help

It’s quite true that they do need extra food then, especially if there is snow or ice during a cold spell. But the spring and early summer months, when they have chicks in the nest, are even more crucial.

So make sure you keep refilling your Birdfy camera feeder to ensure that the parents have an easy supply of food to keep their energy levels up, as they search for natural food for their young.